It’s all in the wrist.

Wrist injuries are lower down on the list of the most common rowing injuries but they are often very hard to get on top of and as such present an often long and frustrating road block in return to sport or at least in reducing capacity.

Wrist and forearm injuries are most commonly of the overuse type and can almost always be related to poor technique or a too tight grip putting the wrist into a poor position while applying force or moving to feather the oar. There are many different sort of wrist and forearm injuries including tendon, muscle, ligament and joint structures but the most common are the tennis/golfer’s elbow type epicondylitis, tenosynovitis and compartment syndromes. Some are so linked to rowing that they have been coined Oarsman’s Wrist (intersection syndrome) and Sculler’s thumb (hypertrophy of the muscles abduct and extend the thumb).

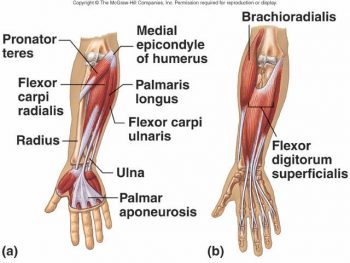

The wrist is made up of 8 small carpel bones that sit in 2 rows of 4 just below the hand, these are joined by the radius and ulna of the forearm and the metacarpels that form the main part of your hand. There are many ligaments and tendon insertions in this area and the movements that the wrist must perform are quite complex – flexion, extension, pronation, supination, devaiations to name a few. As with all body parts the wrist is very much influenced from the joints and structures above and below it. In this case the elbow and shoulder paly a huge role in what the wrist does during the stroke. The Elbow holds the origin of many muscles that insert into or run over the wrist so the arm should really be seen as one linked structure that has hinges at the wrist and elbow.

One of the most common causes for overload at the wrist or forearm is seen with an early elbow break in the stroke. This puts more emphasis on the wrist and muscles surrounding the elbow early in the stroke when the load is always heavier. If you think that at maximum handle force you may be loading 100kg + through the foot stretcher and that this must be transferred into the oar handle/s 200 + times over 2km you can see how, if the wrist and elbow are not well controlled and braced, these structures will be pushed to their limits. As we have said before, whatever moves the fastets or most when applying force is where the load will be transferred to – an early arm draw means you loose force from the feet, often shorten the stroke and certainly increase the load on the wrist and elbow. This will then mean that the wrist cocks into a flexed (in most cases) or extended position to try and continue the arm movement that has started early and to hold onto the handle. If you image the forearm muscles like ropes that run from the elbow down to the wrist, you can see that when the wrist flexes downwards or extends up you are going to lengthen some of these ropes and shorten other, for instance flexing the wrist in the arm draw will relatively lengthen the muscles on the top of the forearm (extensors) while shortening the flexors under the forearm. This means the muscles have more loads on them while they are trying to cope with that 100kg of foot to oar force you are jamming on to get in front of the pesky shell in lane 3.

If you treat the arm as a whole unit and move it as such in a coordinated flow, driven from the shoulder, it will allow more muscles and more control through the arm draw right to the finish. With this method you will have your larger shoulder stabilizing muscles doing more of the work and an emphasis on the load being taken by the larger joints, as well as spreading the force through your body swing and arms – get the bigger structures to do the heavy lifting.

Another issue that is also very frequently linked with what we have described above is an exaggerated handle grip. Grabbing at the handle and crushing it will automatically start to flex and deviate the wrist because of the bony structures under the muscles. That extra grip comes from the muscles in your hand and forearm and there is a cost – before you have taken a stroke you are already loading them up and fatiguing them. An over-strength grip also creates tension high up the arm and we often see the over-gripped rower braking their elbow early with the biceps firing up as soon as load is felt on the handle or the ‘shrugging rower’ who over-grips and as a result builds up a lot of tension in their traps (upper shoulders). Again we see the flow up and flow down effect of how the body’s linked structures work. A heavy grip, tight and traps and early, exacerbated loading of the bicep means more fatigue, less efficiency and even potential effects on breathing mechanics as acute effects. The chronic effects oten hit the weakest or most vulnerable parts first – the wrist and elbow muscle insertions or tendon sheaths.

How to reduce your risk at the wrist….and elbow:

Pick the right sized handle grips

Don’t over-gear the rigging

Focus on your leg drive and body swing in the early phases of the stroke, don’t get the arms involved too early, it can feel strong but it isn’t

Warm up properly – cold muscles, even the small ones of the forearm and hand are not ready for big loads

Get you technique up to speed, concentrate on being an effective rower and watch your injury risk fall away and your speed rise

Keep your wrist and hand flat through the arm draw and relax your shoulders – this is key on the ergo too where it is easy to over-grip

Feather smoothly and don’t extend the wrist too much – being calm and smooth means better boat trim as well

Work on shoulder strength – improving the strength and movement ability of your shoulders will help you a lot, don’t just work on your beach muscles (pecs and biceps) as this makes you more likely to rely on them only

Management:

Establishing what the injury actually is and the primary site is key, then you must pick apart the biomechanics of why it happened – many issues show pain in one area but the cause may not be at the same site of the symptom

Conservative immediate treatments involve ice, relative rest, stretching and deep tissue massage – the massage is something you can do yourself and may also be good as a maintenance to release tight muscles after rowing regardless of pain. Concentrate on the area just below your elbow joint where the more ‘meaty’ parts of the forearm are

NSAID’s or bracing and taping may be indicated but be sure of this – sometimes limiting motion is not the answer and NSAID’s can have many side effects and may not be necessary of the condition is not inflammatory

Addressing the mechanics of the shoulder and wrist joints is often key and once able without aggravation strengthening is usually an important intervention around the site or at mechanically linked areas that may have been causal

With some simple tips you should be happy rowing and maintaining your status as the best arm wrestler in the boat house, pain free.