“So tell me, squats it got to do with injury?”

To squat or not to squat? To squat deep or midrange? Is it safe? There are so many ongoing and evolving discussions in the strength and conditioning world around squatting and gluteal activation, even some launched this week on the merits of the glue bridge vs the deep squat for engagement and hypertrophy. We thought we’d strip it all back and look at a lit review article that gives you confidence to get in the gym and lift with common sense and good technique, and avoid unnecessary and over-publicized fears.

Don’t let anyone tell you that you can’t squat, no matter your age or your athletic ability – modify the exercise to suit your goals and your level but don’t be scared of it. If you can move from a standing to sitting position and back up out of your chair, then you can squat and if more people did then we would see less, not more lower back injuries and, in the elderly population, less falls and more stability.

As we see below, if your range of motion allows you to get low, there is no serious risk in that either.

The following takes in the abstract from a Sports Medicine journal review titled; Analysis of the load on the knee joint and vertebral column with changes in squatting depth and weight load.

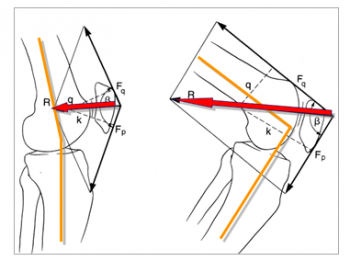

It has been suggested that deep squats could cause an increased injury risk of the lumbar spine and the knee joints. Avoiding deep flexion has been recommended by some to minimize the magnitude of knee-joint forces. Unfortunately this suggestion has not taken the influence of the wrapping effect (the range where the quad tendon begins to contact the femur), functional adaptations and soft tissue contact between the back of the thigh and calf complex into account.

The aim of the review of literature was to assess whether squats with less knee flexion i.e. half or quarter squats are ‘safer’ on the musculoskeletal system than deep squats. The review took in the most recent research between 2011 and 2015. Over 164 articles were included.

There are no realistic estimations of knee-joint forces for knee-flexion angles beyond 50° in the deep squat. Based on biomechanical calculations the highest compression forces from the knee cap and stresses can be seen at 90°. With increasing flexion, the wrapping effect contributes to an enhanced load distribution and enhanced force transfer with lower knee cap compressive forces, not higher. This is because once we begin descending beyond 70 degrees of knee flexion in the squat, the quad tendon begins to contact the femur, thus increasing surface area contact which has the effect of spreading the force.

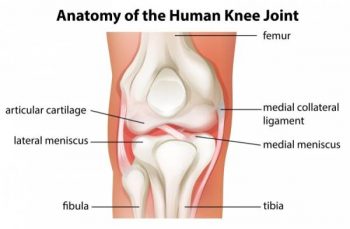

Additionally, with further flexion of the knee joint a an enlargement of the articulating surface occurs with the knee cap and joint. Both lead to lower compressive stresses. Menisci and cartilage, ligaments and bones are susceptible to anabolic metabolic processes and functional structural adaptations in response to increased activity and mechanical influences. Concerns about degenerative changes of the tendofemoral complex and the apparent higher risk for chondromalacia, osteoarthritis, and osteochondritis (what we know as ‘wear and tear’) in deep squats are unfounded. With the same load configuration as in the deep squat, half and quarter squat training with comparatively supra-maximal loads will favour degenerative changes in the knee joints and spinal joints in the long term.

So in summary:

Provided that technique is learned accurately under expert supervision and with progressive training loads, the deep squat presents an effective training exercise for protection against injuries and strengthening of the lower extremity.

Contrary to commonly voiced concern, deep squats do not contribute increased risk of injury to passive tissues.

So do squat, squat deep and engage those muscles over larger ranges if you can control the movement well. We’re for lifting to help rowing!

Article reference base:

Sports Med. 2013 Oct;43(10):993-1008.

Analysis of the load on the knee joint and vertebral column with changes in squatting depth and weight load., Hartmann H1, Wirth K, Klusemann M.